Octopuses on ecstasy drug 'become more social'

Octopuses given the drug ecstasy become more social and try to hug each other, a study has found.

Writing in the journal Current Biology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University in the US say the drug affected the creatures in a similar way to humans.

In normal circumstances, octopuses are solitary animals who can prey on each other after mating.

Scientists say the way they behave while on the drug may give insights into how social behaviour has evolved.

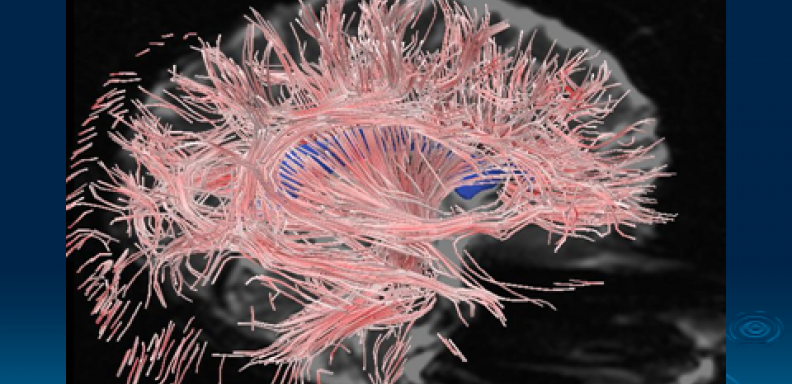

MDMA (methylenedioxy-methylamphetamine), also known as ecstasy, is a powerful mood-altering drug which floods the human brain with a chemical called serotonin.

Serotonin makes people more sociable.

While octopuses are intelligent creatures, their brains are physically very differently to those of humans. For that reason, researchers were unsure how they would respond.

What did the research show?

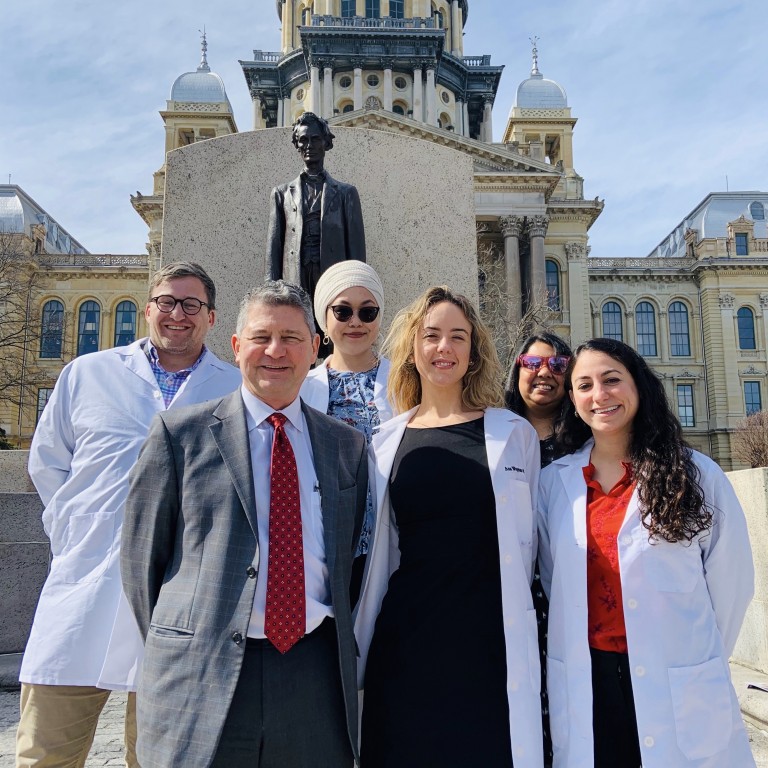

Gül Dölen, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who led the study, designed an experiment with three connected water chambers. One of them contained a trapped octopus, and the other a plastic toy.

Four other octopuses were placed inside the tank to test their response. Researchers measured how long they spent with the other animal, and how long with the action figure.

Then, they were exposed to a liquefied version of MDMA, which they absorbed through their gills, and placed in the chambers again.

The study found that all four spent more time in the area with the other octopus than they had before the drugs.

"They tended to hug the cage and put their mouth parts on the cage," said Prof Dölen.

"This is very similar to how humans react to MDMA; they touch each other frequently," she said.

What does this mean?

The findings suggest brain chemicals may be key to social behaviour across very different species. That applies even though many of the nerve cells that react to serotonin are in an octopus's arms.

"We could say the octopus brain is totally different to a human one, but we need this synapse or this neurotransmitter," Prof Dölen says. "We could write down a list of these minimal building blocks of complex behaviour."

It may not be impressive brain circuitry which underpins social behaviour, then, but basic signalling chemicals.

Other researchers have raised questions about the study's methodology, however. Professor Harriet de Wit from the University of Chicago, who has studied how ecstasy affects animals, said it was "innovative and exciting" - but that we can't be certain the drugs were fully responsible.

Ideally, the experiment would be repeated on a larger scale, the researchers agreed.

And some of the octopuses would be placed in the tank for the first time after absorbing ecstasy, and others would not. Prof de Wit said that would help rule out the idea that they were friendlier the second time because they'd got used to the tank, or the other octopus.