stated on April 14, 2023 in a speech to the National Rifle Association:

"In the 1960s, liberals emptied our psych wards."

Former Vice President Mike Pence speaks April 14, 2023, at the National Rifle Association Convention in Indianapolis. (AP)

By Louis Jacobson April 20, 2023

Mike Pence said ‘liberals’ emptied mental health hospitals in 1960s. They didn’t act alone.

IF YOUR TIME IS SHORT

- Some of the impetus for moving people with serious mental illness out of institutions in the 1960s came from legislation signed by Democratic presidents and supported by civil rights advocates.

- But fiscal conservatives, many of them Republicans, also played a crucial role — notably Ronald Reagan, who signed landmark legislation, first as California’s governor and then as president.

See the sources for this fact-check

During the National Rifle Association’s recent annual convention, former Vice President Mike Pence decried attempts to tighten gun laws, focusing instead on policies that address mental illness.

"With so much violence taking place at the hands of those with severe mental illness, the answer to mass shootings is not fewer guns, it's more institutional mental health in this country," Pence said April 14 in Indianapolis.

He continued: "In the 1960s, liberals emptied our psych wards, only to fill our streets and ultimately our prisons with the mentally ill."

For this fact-check, we focused on Pence’s assertion that "in the 1960s, liberals emptied our psych wards."

Multiple experts told PolitiFact that blaming liberals, or Democrats, for shutting down mental health institutions is a vast oversimplification of a far more complicated history.

Experts said that one of the leading figures in this effort was a conservative icon, Ronald Reagan, both as California’s governor and as president. Other key players in the policy shift included the U.S. Supreme Court and governors and legislators from both parties who saw an opportunity to save money by shuttering inpatient institutions.

Pence’s statement is "inaccurate and unfortunate," said Daniel Yohanna, a University of Chicago Medical Center associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience. Yohanna called Pence’s statement "overly simplistic" and said it "puts blame on the people that have little to do with mass shootings."

Pence’s staff did not respond to inquiries for this fact-check.

Mental health care in the United States: A brief history

Societies have long struggled with how to treat people with severe mental illnesses.

"There is no perfect solution," said Alex Cohen, a Louisiana State University psychology professor. He said inpatient hospitals are expensive and don’t necessarily help people return to independent lives. Outpatient care is less expensive and often produces better results, but still requires funding. And prisons, where a large number of mentally ill people end up today, is both expensive and terrible for recovery.

Since at least the 1930s, Cohen said, policymakers have sought to cut costs through "de-institutionalization" — removing people from inpatient settings. This accelerated during the 1950s, with the advent of antipsychotic medications. These medications significantly reduced symptoms for people with conditions ranging from schizophrenia to bipolar disorder and improved their chances at finding jobs and participating in their community.

Much of the shift to deinstitutionalization occurred after passage of two pieces of legislation under Democratic Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

The first law, enacted in 1963, was the Community Mental Health Act, which aimed to fund community-based treatment facilities as an alternative to institutionalization. The second law, enacted in 1965, was Medicaid, which made payments to "institutions for mental diseases" ineligible for federal reimbursement.

From 1955 to the 2010s, state and county psychiatric institutions’ resident populations fell by 93%, from more than half a million to about 37,000.

Kennedy and Johnson’s role in deinstitutionalization provides some support for Pence’s statement. During their presidencies, protections for marginalized groups such as racial minorities were expanded, and some Democrats also pushed to expand civil rights for the mentally ill.

However, experts agree that the coalition that supported moving away from institutionalization was much broader than just "liberals." For one thing, there was widespread public revulsion at the conditions inside the institutions.

Institutions, especially "custodial care" units with patients who were not expected to improve, were overcrowded, and neglect and abuse were not uncommon, said David Mechanic, an emeritus professor at Rutgers University’s Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research.

FEATURED FACT-CHECK

Medical professionals largely agreed that medical advances made outpatient care more promising, which accelerated the shift away from institutional care.

Cost savings was a big factor

The biggest driver of deinstitutionalization may have been money.

"There is no doubt that a major cause of deinstitutionalization was the eagerness of state governments to save money by shutting down mental hospitals," said Christopher Slobogin, a Vanderbilt University law professor and affiliate professor of psychiatry.

The prospect of cost savings appealed particularly to fiscal conservatives.

"State-based fiscal conservatives wanted to reduce the population of state-operated mental hospitals" so they could shift some of the cost to federal government programs like Medicaid, said Howard H. Goldman, a University of Maryland School of Medicine professor of psychiatry.

California was a pioneer in this approach. In 1967, then-governor Reagan signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which narrowed the circumstances under which residents could be involuntarily committed for psychiatric treatment. The California bill was named after a liberal legislator, Petris, and a conservative legislator, Lanterman, said Dan A. Lewis, a Northwestern University human development and social policy professor.

"Conservatives were concerned about the costs of involuntary commitment and the reduction of personal freedom involved, and liberals hated the poor treatment in state hospitals and the huge waiting lists for commitment," Lewis said. "There was consensus about making the change."

A key reason for deinstitutionalization’s failures was a lack of sufficient funding for the alternative — community-based care, which includes outpatient care, day treatment, supported employment and housing and case management, said Lonnie R. Snowden, a professor with the University of California-Berkeley School of Public Health

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the Mental Health Systems Act, which sought to bolster federal assistance for the care of people with chronic mental illness. But Carter lost reelection that November, and the following year, Reagan — then the president — signed a budget bill that repealed virtually all of the act’s provisions and effectively cut funding by about one-third.

In time, "prisons became the alternative mental hospitals," Rutgers’ Mechanic said.

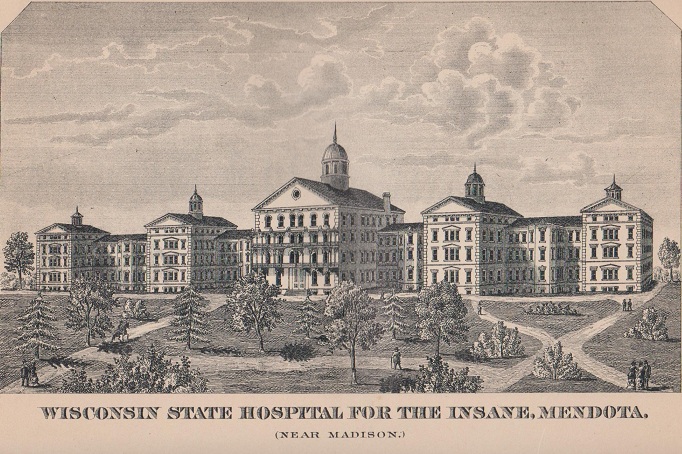

The Wisconsin State Hospital for the Insane, from the 1885 Wisconsin Blue Book. (Wikimedia Commons)

Would it be possible to reinstitutionalize the seriously mentally ill today?

Experts agreed it would be unrealistic to return to mass institutionalization.

The law likely wouldn’t allow it, given several U.S. Supreme Court decisions that raised the threshold for involuntary commitment, including O’Connor v. Donaldson in 1975 and Addington v. Texas and Parham v. J.R. in 1979.

"It would probably be impermissible to continue to hold someone who has been successfully treated with medication, unless it can be shown they will go off their meds once released," Vanderbilt’s Slobogin said.

Even if mass institutionalization were to return, it’s unlikely to reduce violence enough to outweigh the financial and societal costs, said Linda A. Teplin, vice chair for research in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. Because the vast majority of people committed would be nonviolent, she said, it would neither be cost-effective for reducing crime nor beneficial for the health of the people who would be institutionalized.

"Substance use, inequality and lack of opportunity, and access to guns are the major drivers of violence," rather than mental illness in a vacuum, Cohen said. Blaming serious mental illness "is just a diversion tactic."

Ultimately, Cohen said, "the failures" of deinstitutionalization "don’t fall on any party."

Our ruling

Pence said, "In the 1960s, liberals emptied our psych wards."

Some of the impetus for shifting people with serious mental illness out of institutions came from legislation signed by Democratic presidents and supported by civil rights advocates.

However, fiscal conservatives also played a crucial role, including Reagan, who signed landmark bills, first in California and then for the nation. Other key players in the policy shift included the U.S. Supreme Court and governors and legislators from both parties who saw an opportunity to save money by closing inpatient institutions.

The statement is partially accurate but leaves out important details. We rate it Half True.

Our Sources

Mike Pence, remarks at the National Rifle Association convention in Indianapolis, April 14, 2023

H.H. Goldman, R.G. Frank, and J.P. Morrissey, editors, "The Palgrave Handbook of American Mental Health Policy," Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2020.

Daniel Yohanna, "Deinstitutionalization of People with Mental Illness: Causes and Consequences" (AMA Journal of Ethics), October 2013

Joni Lee Pow, Alan A. Baumeister, Mike F. Hawkins, Alex S. Cohen, and James C. Garand, "Deinstitutionalization of American Public Hospitals for the Mentally Ill Before and After the Introduction of Antipsychotic Medications" (Harvard Review of Psychiatry), May-June 2015.

Grant H. Morris, "The Supreme Court Examines Civil Commitment Issues: A Retrospective and Prospective Assessment" (Tulane Law Review), 1986

Blake Erickson, "Deinstitutionalization Through Optimism: The Community Mental Health Act of 1963" (American Journal of Psychiatry), June 2021

H. Richard Lamb and Linda E. Weinberger, "The shift of psychiatric inpatient care from hospitals to jails and prisons" (Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law), 2005

State of California, Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, 1967

Congress.gov, Mental Health Systems Act, 1980

Supreme Court, O’Connor v. Donaldson, 1975

Supreme Court, Addington v. Texas, 1979

Supreme Court, Parham v. J.R., 1979

American Psychological Association, "Mental illness and violence: Debunking myths, addressing realities," April 1, 2021

MentalIllnessPolicy.org, "Medicaid, Mentally Ill, and state hospitals," accessed April 19, 2023

Health Works Collective, "What Is Community-Based Treatment for Mental Illness?" Dec. 23, 2021

New York Times, "How release of mental patients began," Oct. 30, 1984

Cal Matters, "Hard truths about deinstitutionalization, then and now," March 10, 2019

Mother Jones, "Timeline: Deinstitutionalization And Its Consequences," April 29, 2013

KQED, "Did the Emptying of Mental Hospitals Contribute to Homelessness?" Dec. 8, 2016

Email interview with Alan Baumeister, psychology professor at Louisiana State University, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Linda A. Teplin, vice chair for research in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Lonnie R. Snowden, professor with the University of California-Berkeley School of Public Health, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Dan A. Lewis, professor of human development and social policy at Northwestern University, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Howard H. Goldman, professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Christopher Slobogin, Vanderbilt University law professor and affiliate professor of psychiatry, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Alex Cohen, psychology professor at Louisiana State University, April 18, 2023

Email interview with Daniel Yohanna, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago Medical Center, April 18, 2023