By Author Maureen Searcy https://mag.uchicago.edu/science-medicine/measure-pleasure

The University of Chicago Magazine Summer/21

You probably know people who can “hold their liquor,” who can drink a “lightweight” under the table and seem completely fine. Sometimes tolerance comes from individual body size and chemistry, but sometimes tolerance is from practice. Just as weightlifters can lift increasingly heavier weights, people who drink a lot can often drink progressively more before feeling or appearing intoxicated.

This increased tolerance has long been linked to how alcoholism (clinically called alcohol use disorder, or AUD) develops. The prevailing theory has been that heavy drinkers must drink more to feel good, leading to a cycle of progressively higher tolerance and ever-increasing consumption. But that theory has a blind spot: only tolerance to objective adverse effects, like drowsiness, nausea, and lack of coordination, had been observed. Tolerance to the subjective pleasant feelings of being drunk—giddiness, euphoria, relaxation—had never actually been studied on its own, just assumed.

What if the assumption is wrong? What if, wondered UChicago psychologist Andrea C. King, those happy feelings never dampen? Over nearly three decades of treating patients with substance use disorders, she’s noticed that how much her patients like drinking doesn’t diminish over time. In fact, talking one-on-one with them, she learned that many chronic drinkers start feeling euphoric quite soon after their first glass.

King began to question the adage of addiction. If the intention of drinking alcohol is to feel good, and chronic drinkers do not need to drink more and more to feel good, then how can tolerance be driving alcohol addiction? Yet she had only anecdotes. King would need data to find out if excessive drinkers truly were not building tolerance to alcohol’s pleasing effects.

The possibility that those with AUD continue to enjoy drinking, while they and those around them bear the burdens of the disorder, is the elephant in the room, says King. Talking about the euphoria of substance use, even in the context of therapy, remains taboo, so research into the topic is scarce. But to effectively treat and prevent AUD, scientists need to better understand what exactly is happening when social drinkers become alcoholic drinkers, and who is vulnerable to that shift. That means unbraiding the physical, psychological, and social strands of alcohol use and following one thread to the end—and back to the beginning.

Launched by King 17 years ago, the Chicago Social Drinking Project was the first and thus-far longest running study to isolate and investigate the pleasurable effects of alcohol by seeing how people’s happiness while drinking changes over time. The project, persevering even through a global pandemic, has revealed valuable and surprising insights into how a person’s response to alcohol relates to current and future alcohol use disorder.

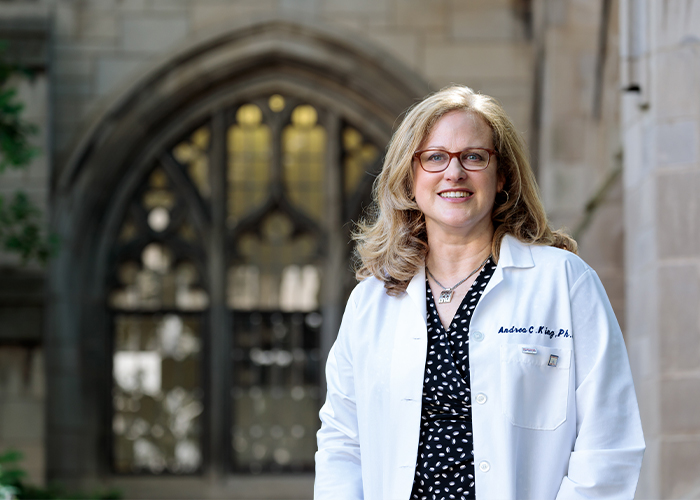

“I’m not unlike many people out there,” says King, who is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience and directs the Clinical Addictions Research Laboratory. “I know people, have family members, with these disorders; the toll they take on themselves and the people around them, the lost productivity, wages, years of life. It’s devastating.”

In 2019 a quarter of Americans 18 and older reported binge drinking (about 4–5 drinks in under two hours) in the past month. And a new trend called “high-intensity drinking” emerged, where people drank at least double what’s considered binging. In 2010 alcohol misuse cost the United States $249 billion, and each year an estimated 95,000 people die from alcohol-related causes. In 2019 alcohol was a factor in 28 percent of all driving fatalities.

King’s early experiences with this devastation have had a major influence on her current work. During her senior year of high school, a classmate was killed by a drunk driver. In college, she watched her fellow students binge drink, “wanting to be executive alcoholics.” And in graduate school, King worked in a treatment program at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Oklahoma City, where she saw the extreme end of substance use disorders. She knew that to better treat patients, she needed to better understand the trajectory of addiction.

Today King treats patients about half a day per week in UChicago’s psychiatry outpatient clinic—mostly people looking for help with alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or other substance use. (She used to have a more even split between practice and research, but the latter has increasingly occupied her time.) “I think treating patients myself helps ground me,” she says, and the complexity of their disorders humbles her.

From those struggling with alcohol, she often hears: Why did this happen to me? Why not to my drinking buddies? King doesn’t have a definitive answer. Some people are more likely than others to develop AUD—the “playing field isn’t even,” she says. But no one knows precisely why some people are more susceptible to alcohol addiction. Genetic predisposition, drinking at an early age, a history of trauma—there’s a constellation of possible causes. Scientists can’t yet fully explain what leads to alcohol use disorder, but they can identify characteristics that might help drinkers figure out how vulnerable they are.

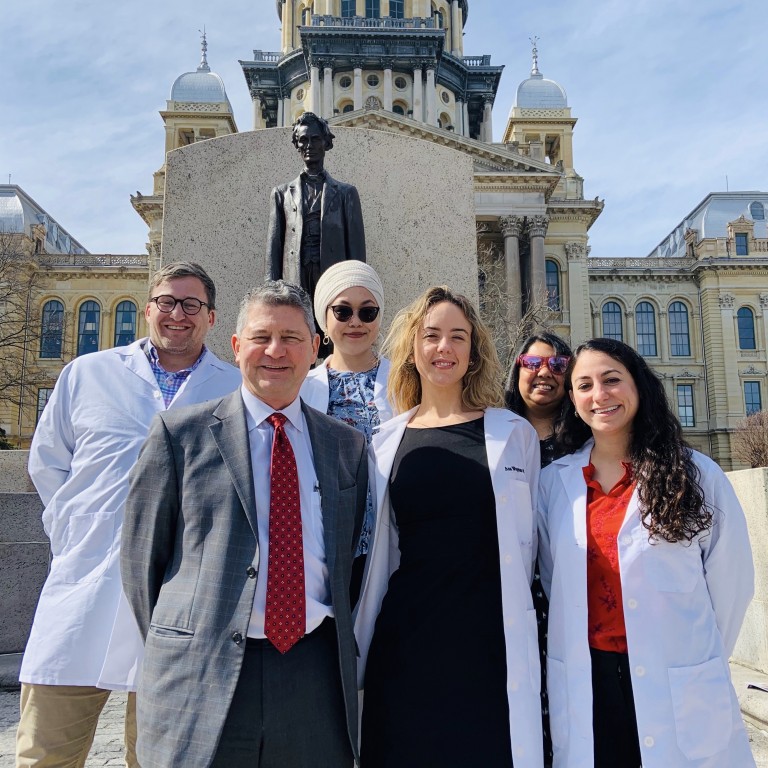

The Clinical Addictions Research Laboratory was established in 1997 under the direction of psychologist Andrea King. (Photography by John Zich)

How good a person feels while drinking could be one trait that foretells AUD, and how those feelings evolve could shed light on the disorder itself. The Chicago Social Drinking Project follows a cohort of drinkers as they age to study physical and psychological responses to alcohol in real time and to search for patterns.

In 2004 King’s team recruited 190 light, moderate, and heavy drinkers in their 20s to follow for as many years as possible. Participants initially attended two double-blind laboratory-based binge-drinking sessions (see “The Challenge” below), where they drank alcohol or a placebo and answered questions about how stimulated or sedated they felt, and also whether they liked or wanted more of the drink.

This process was repeated after five and 10 years for those still eligible (who had not, for example, developed medical or psychiatric conditions that would make drinking dangerous, were not pregnant or nursing, and had not stopped drinking completely). King’s team also interviewed the participants via phone, internet, or mail nearly every year to track whether and when AUD symptoms emerged.

The data revealed a correlation: the young adults with heightened sensitivity to alcohol’s pleasurable effects (stimulation, liking, and wanting) were more likely to develop AUD as they progressed to middle age. For those who did develop alcoholism, how much they liked alcohol started high and remained stable over time. They did not become desensitized to how much they enjoyed drinking. And their levels of stimulation and wanting grew higher—for those responses they became even more sensitive to alcohol.

These results square with anecdotal observations from her practice, contesting the long-held notion that tolerance is the key to AUD, a theory that has “guided the thinking among clinical research for decades.” Rather, the pattern “fits a picture of persistent pleasure seeking,” King has said. If a person’s response to alcohol is quick and pleasant, it fuels their desire for more, and that leads to excessive drinking.

The Chicago Social Drinking Project’s analysis of sedation also offered surprising insight. Prior studies have shown that heavy drinkers can develop tolerance to fatigue. (King’s collaborator Daniel Fridberg, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience, describes meeting a lucid and coordinated patient whose blood alcohol content at the time was almost triple the legal limit.)

Those studies seem to support the prevailing theory of tolerance-linked addiction, says King, as fatigue is protective against excessive consumption; if you fall asleep, you stop drinking. “Stimulation and reward are an accelerator pedal. Sedation is your brake pedal.” People who progress to AUD have faulty brakes. Yet in King’s study, those who developed AUD felt less sedation from the beginning. Their levels of fatigue remained low and stable over time and did not predict future alcohol use disorder. Their brake pedals didn’t wear out from use—they were defective from the start.

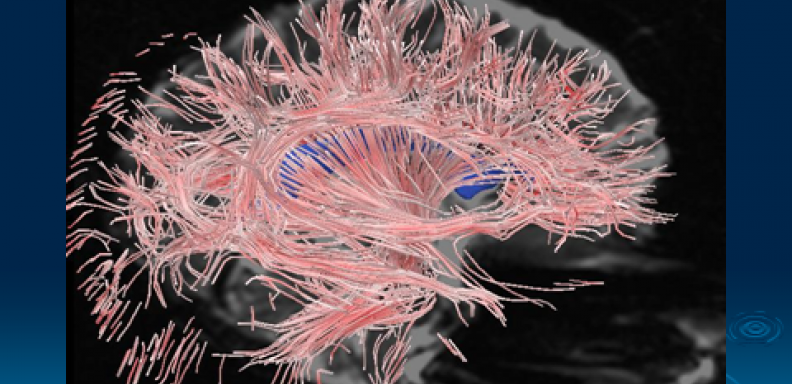

There have been neurological studies designed to see whether alcohol has different effects on people who feel stimulated versus sedated. In one such study, published in 2018, Harriet de Wit, professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience, administered alcohol and a placebo intravenously to healthy volunteers as they underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging, which measures small changes in blood flow that show brain activity.

When people reported stimulation, those feelings correlated with activity in the striatum, “a region of the brain that’s associated with motor function and also with reward,” says de Wit. But when people reported feeling sedation, there was no correlated brain signal in the same area of the brain. These results indicate that feelings of stimulation and sedation aren’t simply an issue of personal interpretation; “there’s a neurobiological basis for some people feeling stimulated by alcohol and other people feeling sedated,” says de Wit, “it actually affects their brain differently.”

Another aspect of addiction research describes a tipping point where drinking for fun gives way to drinking for relief, to stave off withdrawal, leading to a downward spiral. The premise is that the brain’s reward system gets altered by substance use. But King always wondered whether the positive reinforcement actually disappears. What if both motivations exist at the same time?

Until the Chicago Social Drinking Project, experimental alcohol studies didn’t focus on the rewarding effects of alcohol. The clinical lore that those with AUD don’t like or want alcohol anymore is based on ad hoc reports from patients entering treatment—that’s why they’re seeking treatment, after all. But King suspects those feelings are manifestations of regret over what alcohol has done to their lives rather than a negative response to alcohol itself. Her experiment assesses a person’s acute response to intoxication isolated from emotional response to consequences.

King’s study makes the possible more plausible: that the tipping point of addiction is actually a splitting point, where a person with AUD drinks to excess both for pleasure and for relief from negative feelings or withdrawal. The correlations identified by King’s lab could lead to a paradigm shift in how researchers think about alcohol addiction.

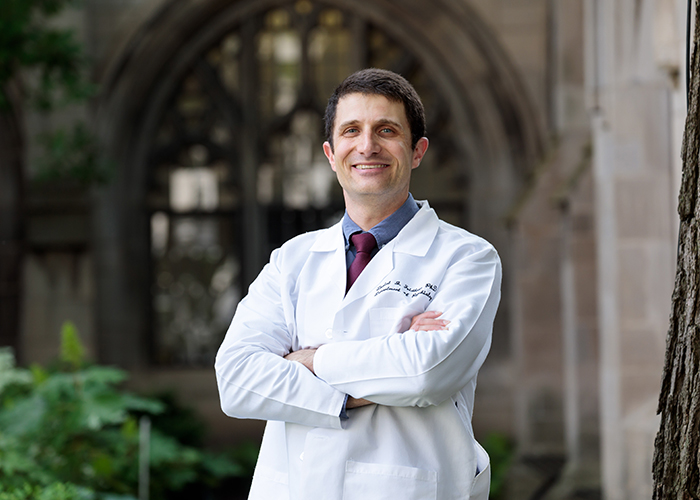

As the codirector of UChicago’s transplant psychiatry program, Daniel Fridberg conducts evaluations for many liver transplant candidates. (Photography by John Zich)

There is no cure for substance use disorders—treatment, therapy, remission, but no cure. So an ounce of prevention is infinitely more valuable. The Chicago Social Drinking Project hopes to improve preventive interventions—to inform people of their personal alcohol sensitivity to help them address their drinking appropriately, says King. Armed with this information, they can judge whether to pay attention to drinking patterns, cut back, or quit altogether. Customized intervention works: King’s team ran a separate pilot study six years ago where two groups of people were brought in for binge-drinking alcohol challenges, as described below, but only one group received personalized feedback.

“We showed them graphs of their alcohol responses and told them, ‘We’re studying a cohort long term, and people who had this response in their 20s were at much higher risk to become alcoholic by their 30s,’” says King. “You get 23-year-olds looking aghast at you.” Her team also offered that group techniques to cut back on drinking. The control group was given only the techniques. Six months later, the personalized intervention group had a 50 percent reduction in binge drinking over the standard intervention group.

King and Fridberg also collaborated with a researcher who tested German 18- and 19-year-olds (prohibited in America because of legal restrictions on alcohol for minors). After a small IV alcohol infusion, the teens could press a bar for as much alcohol as they wanted—up to a safety limit. Their responses mirrored those of their older American counterparts. Sensitivity to alcohol’s pleasurable effects may be present very early in life, when many people first start drinking, suggesting those younger than the legal drinking age may benefit from interventions.

King compares alcohol response assessment to a cholesterol test. Knowing your cholesterol levels informs behavior: you may need to adjust your diet and exercise. If you have a high sensitivity to alcohol’s pleasing effects, you may need to pay more attention to your drinking patterns. But it’s not practical to run lab sessions as a preventive measure; concerned drinkers need a feasible way to gauge their risk in the real world. So King and Fridberg created a smartphone-based approach to assess people’s drinking in their natural settings.

The Mobile Alcohol Response Study asked drinkers questions via a smartphone app during the first three hours of a drinking episode and more the following day.

Participants repeated the process with nonalcoholic drinks as a control; that’s one of the few factors King and Fridberg can regulate with the smartphone model. Other rigorous experimental controls used in lab-based sessions are impossible. But it’s an interesting extension of their work; “people in their own environments drink at different paces, different levels.” The study can track how low- and high-risk drinkers respond to alcohol in different contexts, says King. “So we’re getting into messy territory.”

That messiness is “part of the appeal,” says Fridberg. It reflects the real world’s untidiness. In a controlled lab setting, everyone sits in the same chair, has the same drink, talks to the same research assistant, he says. “You’re eliminating the fact that this person who was out drinking got in a fight with their friend; this person was on a first date and was excited; this person vomited.” You can minimize those factors and isolate the alcohol effects.

Yet people do go on first dates and they do get physically ill. They “don’t drink the equivalent of four to five standard drinks, stop, and then ride out the curve,” says Fridberg. “They may drink very intensely—up to seven or eight or even 12 drinks over three hours,” says King. “We see really high levels of intoxication.”

Most research on real-world drinking patterns is based on memory, but the very nature of what’s being studied—intoxication—makes such reporting unreliable. The smartphone-based assessment lets researchers collect data on behavior and reactions in real time. “It’s a great technology to harness for this purpose,” says Fridberg. “Everyone has a phone, they know how to use it, and they look at it multiple times an hour.”

After a 2019 pilot study showed that heavy drinkers were willing and able to use the app, Fridberg and King are now analyzing the data collected. The ability to directly compare how people respond in their natural environments to their responses in the laboratory is new terrain, says Fridberg. They’re also testing people with AUD using the smartphone model to compare with the pilot group of heavy social drinkers, says King. And they’re enrolling excessive drinkers with clinical depression or anxiety to further test the notion that they drink to relieve negative emotions but may still experience heightened enjoyable effects of alcohol.

In her practice, King uses a self-monitoring method to raise a patient’s awareness of alcohol response. A woman in her mid-30s who had dealt with depression since childhood found herself drinking too much on the weekends, consuming a three-liter box of wine by herself. King asked her to document her responses after each alcoholic drink and to consider her reasons for wanting more. The patient “noted a relief in negative mood but also a positive and energetic feeling after a few drinks, which led to more drinking.” She didn’t want to abstain completely from alcohol, but working with King to understand how her alcohol sensitivity might eventually lead to addiction and worsening depression, she was able to set boundaries. After two years of therapy, she was having a couple of drinks a week but in low-risk situations, with friends or away from home.

Harriet de Wit studies the subjective, behavioral, and physiological effects of drugs of abuse. (Photo courtesy Harriet de Wit)

Results from the Chicago Social Drinking Project could also influence treatment for people currently living with alcohol use disorder, which is a spectrum with mild, moderate, and severe levels. Many people with AUD are recommended a 12-step program like Alcoholics Anonymous, says King, but treatment specialists are becoming more open to medications and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Currently there are four medications approved for AUD. One such drug is thought to work by blocking endorphins; another prevents the body from metabolizing alcohol, causing the drinker to feel ill. They have drawbacks, including low rates of compliance, and no new medications have been approved for decades.

Several medications in early phases of development are aimed at easing physical withdrawal, but King would like to see more designed to block or weaken alcohol’s feel-good effects.

Some patients need a combination of approaches. Another of King’s patients—a man in his early 40s with a 22-year history of excessive drinking—had some success with therapy and medication but, like many in treatment, had setbacks. One relapse began in a hotel lobby bar. “When seeing all the liquor bottles, he noted, ‘that would be awesome!’ and proceeded to have a three-day drinking bender.” They discussed how he may react more strongly to cues than others, and when he drinks, “his brain reward pathways are quickly activated.” That understanding has helped him avoid and manage triggers.

Fridberg is particularly invested in AUD treatments; as the codirector of UChicago’s transplant psychiatry program, he conducts psychological evaluations for candidates, working with people facing one of the worst outcomes. Many patients he sees are waiting for a liver transplant, and almost all of them, he notes, were heavy drinkers.

He cites a retired man who had evidence of cirrhosis. He understood the physical harm of heavy drinking, “but there was a lot that he liked about drinking as well.” So they addressed what made him happy: he enjoyed socializing with friends and neighbors, and alcohol was usually present. Then they talked about how the man wanted to live the rest of his life. He had grandchildren and wanted to stay healthy enough to watch them grow up. That mindset helped convince him to stop drinking.

Early in his work with the transplant team, Fridberg lost one of his best friends to alcohol-related liver disease at 33 years old. “We were so young at that time and that event really opened my eyes to the importance of working with these patients, no matter where they are in terms of their desire to change their drinking,” he says. “I think about my friend every time I do a pre–liver transplant evaluation or work with a patient with an alcohol use disorder.”

To say that AUD is complex is an understatement. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention won’t be easily revised, King acknowledges. “Implementation science is a big field; just because something’s published in a paper in 2021 doesn’t mean everyone’s going to start doing it in 2022.” To incorporate the team’s findings into standard interventions, “You’d probably need to show more robust effects across independent labs using the same measures,” says Fridberg.

Fridberg and King hope to add new dimensions to their work by incorporating more objective measures. For the smartphone study, they considered asking drinkers to use a breathalyzer, but the devices are intrusive, conspicuous, and, most importantly, inaccurate if used incorrectly. “Most people don’t realize that to get an accurate reading, you have to wait 15 minutes after your last drink,” says Fridberg, “and rinse your mouth out thoroughly with water so there’s no residual mouth alcohol contaminating the data.”

About 1 percent of the alcohol you drink passes through the skin and can be measured with a transdermal sensor, like law enforcement ankle monitors, but biosensors aren’t perfect either. There’s up to a 45-minute delay between drinking alcohol and sweating it out, and transdermal alcohol concentration isn’t easily translated to blood alcohol concentration. But “the field has gotten really excited about these devices,” says Fridberg; they open the door to new types of alcohol studies.

Meanwhile the Chicago Social Drinking Project continues to answer questions—and raise new ones. The assumption that positive effects diminish and addiction becomes the burden of chasing relief isn’t supported by King’s work, but maybe she hasn’t tested this cohort long enough. Maybe in another five, 10, 20 years, she says, these same individuals’ pleasure response will “flatten out.”

The original cohort would probably be willing to put in another 20 years. The project has had an extraordinary level of retention: 99 percent of still-eligible participants returned for the 10-year follow-up. King’s team went beyond basic logistics to keep people coming back. “Some couldn’t leave their dog at home, so we covered pet care,” she says. They formed relationships; King sent birthday and holiday cards and quarterly newsletters. “We really wanted them to know this is a partnership.”

The team is three-quarters of the way through the follow-up interviews between years 11 and 15, so they will complete that wave, but King has decided not to bring the original group back to the lab. “They have kids and lives, and they’re all over the globe now.” She’s asked enough of them.

And, through participation in the project, some have stopped drinking. One man in his late 30s, who had been in the study nearly half his life, conducted his 15-year follow-up interview in 2020: “I have been sober for two years now,” he reported, “and I am pursuing training in counseling so that I can help others with drinking issues.”

King may be giving her original cohort a break, but she’s in it for the long haul. Her lab plans to start a new study with a different, older group—people who have already lived with AUD for 20 years or more—and compare their responses to light and moderate drinkers of the same age. She also has a second replication cohort of heavy drinkers, about five years behind the first group from 2004, who will complete eight- and 10-year follow-ups. “It’s not for the faint of heart,” she says, to keep doing the same thing for that many years. But to confront a condition as complicated, comprehensive, and prevalent as alcohol use disorder, “you have to be ready for the long fight.”

In a controlled laboratory setting, researchers can isolate pure alcohol effects. (Photo courtesy Andrea King)

The challenge

Chicago Social Drinking Project participants attended two lab-based binge drinking sessions separated by at least 24 hours. The lab was set up like a living room, with magazines and a television, and a research assistant for company. The setting mimicked a natural drinking scenario, like an evening relaxing at a friend’s house, but was also controlled so that the researchers could focus on the alcohol effect.

Participants were asked to drink a beverage during the first 15 minutes of the four-to-five-hour visit. In one session, the drink had enough alcohol for the person’s blood alcohol level to reach around 0.1 percent—over the legal drinking limit. In the other, the same person was given a drink with just enough alcohol to disguise its placebo identity but not enough to produce noticeable effects. Neither the subject nor the research assistant knew what the drink contained. (If they knew which one was alcoholic, their response might be influenced by how they expect to feel while drinking alcohol.)

The drinkers answered questions about how stimulated or sedated they felt throughout the session, scoring themselves based on adjectives like elated, sluggish, and energized. They were also asked whether they liked how they felt (in the researchers’ language, hedonic reward) and whether they wanted more of the drink (motivational salience), rating themselves from 1 to 100.

Liking and wanting are difficult to quantify, and it’s tricky to isolate the pure alcohol effects. Maybe one person prefers the taste of certain spirits over others. King controlled for personal preferences by serving drinks that tasted “terrible,” she says. “I can’t even tell you how bad it is. It’s Everclear with Kool-Aid.” (Some have likened the sucralose-sweetened drink to cough syrup.) “It’s not anything most people would want to drink, so when they say they like it and want more, they really like and want the effects.”

Participants were sent home via a car service.

To learn more about the work of the Clinical Addictions Research Laboratory, visit addictions.uchicago.edu.